Translation: Axelle Ropert on How Do You Know

As a companion to our piece on James L. Brooks’ How Do You know, we are also publishing two translations. One is a review by Axelle Ropert published around the time of the film’s release in France. And another is a fragment of an interview that Axelle Ropert gave to Fiches du Cinema that touches on the film and James L. Brooks in general.

A miraculous balance between comedy and melodrama. An unparalleled intelligence in understanding human feelings. A splendor.

Don’t be fooled by the poster or the title that sells an anonymous comedy - How Do You Know is quite simply the most wonderful film of the new year.

James L. Brooks is not an unknown, even if he makes few films (six films in 27 years), undoubtedly because of the absolute attention to detail of his cinema, which devours time.

A refined filmmaker, yes, which does not make him a bedside filmmaker of the intelligentsia, but rather a secret godfather of American entertainment (Apatow reveres him), a bit like McCarey and Rohmer inspire respect in all: we have the right not to adore their films, but their art displays a mysterious and incontestable form of integrity.

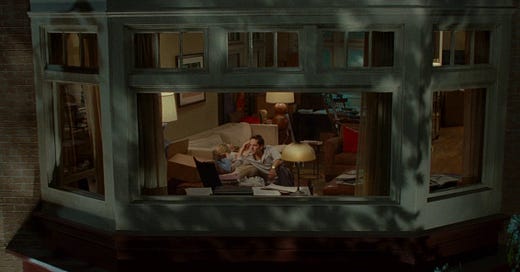

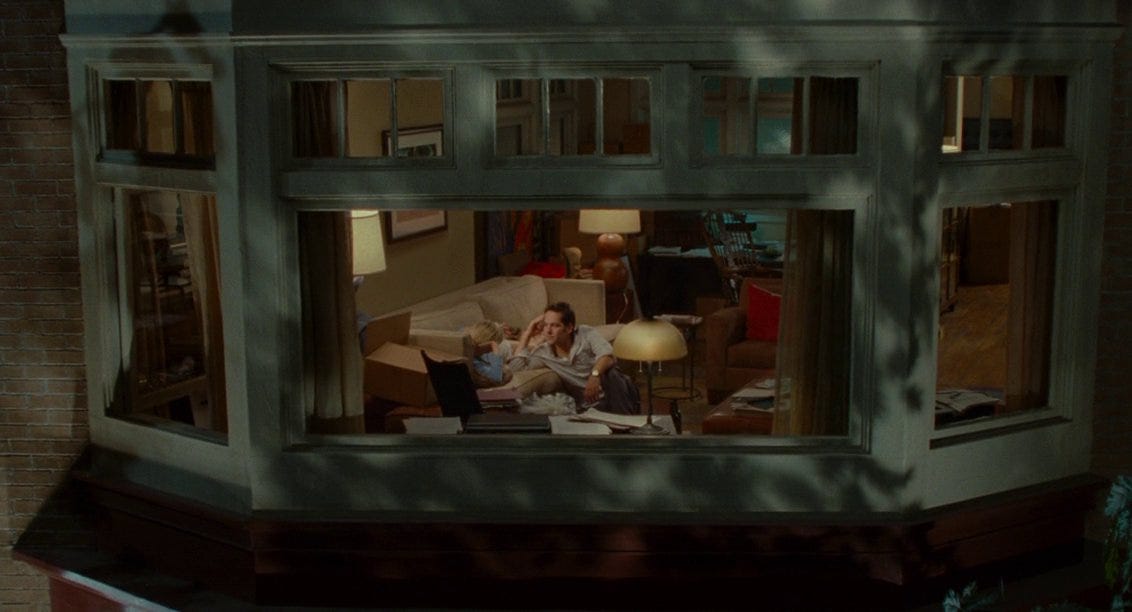

The big words are thrown around, while How Do You Know moves forward little by little and only gradually reveals its grandeur. A declining athlete gets kicked off the national softball team. She meets a baseball player on the rise and a businessman on the decline. Who will she choose?

Reese Witherspoon plays the sporty chihuahua, Owen Wilson is the super selfish idiot jock, Paul Rudd is the daddy’s boy (Jack Nicholson) on whom the world collapses.

Feminine vivacity, idiotic but vigorous masculine blondness, anguished but tender masculine brownness, constantly rub against each other, agitated by a question that the in-tune spectator will identify at the same time as the characters.

The question is profoundly American: according to what dosage of optimism and pessimism should we approach life? Basically, more than between two men, this is what Reese Witherspoon must choose, a Rohmerian heroine who has forgotten metaphysics (too European for the film) for practical psychology (we are in the United States). She is at the crossroads in her life: should she go towards the optimistic, comforting but grumpy man, or the pessimistic, intelligent but anxious man? AT teh end of the two hours of the film, we will know.

Thus, while most current comedies adopt a more random rhythm, Brooks’ films move forward according to questions that constantly metamorphose to find their best formula: when the best formula is found, the film can stop.

The scenes are constantly corrected: if Reese Witherspoon announces herself at first as a mommy (she disapproves of the feminist tone of Kramer vs. Kramer), she says a few moments later that the idea of forming a family scares her.

It is always the second time that the truth comes out, because to be accurate, it takes time, you have to go through the words. And the film takes time: an organic duration so that the fiction can finally shimmer, fully exposed in its details.

Where things get complicated is that the optimist and the pessimist continue to make efforts to be a little less so: Owen Wilson tries to shade his bliss with concern, Paul Rudd strives to offer a smiling face. How Do You Know is a comedy of virtuous efforts where it is not a question of behaving well, but of being as rightly happy as possible: a question of infinite subtlety, because how do you know?

Brooksian characters are people who can’t help being who they are and who make you laugh with the stubbornness of their character. But these are also characters who do something to no longer be what they can’t help but be, and this effort to change is as moving as a child’s first steps: each time, it’s as if a new era was beginning.

Victory is always fragile, subject to relapse, and quivering. Otherwise, the film is super funny (watch out for Wilson’s “good talk”) and we obviously won’t tell you who comes out the winner, or rather, happy.

« Comment savoir », petite merveille de finesse et d'humour was published in the magazine Les Inrockuptibles, in January 2011. Translation by Jhon Hernandez

This year, there have been a number of films that have divided critics, and more generally, the cinephile sphere. But as much as some of them (like The Tree of Life, Polisse, or Shame) created confrontation, others (like Super 8 or How Do You Know) functioned more as a sign of recognition between those who loved them passionately. Did you feel this in relation to the last film by James L. Brooks which you fervently defended in Les inrockuptibles?

How Do You Know was, in fact, not received in a mostly positive way… I have the impression that today James L. Brooks has a somewhat complicated status. He experienced a peak of notoriety in France 30 years ago with Terms of Endearment, then another around 15 years ago with As Good as it Gets. But then, Spanglish, released in 2005, went completely unnoticed in the press and was a flop in theaters. Maybe Brooks suffered from the arrival of a trashier section of American comedy, no longer based at all on the sophistication of the plot and dialogues, but on a certain “enormity” of things: basically, the arrival of the Farrelly Brothers, then the Judd Apatow school, and that apparently made his work obsolete. In this sense, I would compare him to a French filmmaker, Pierre Salvadori, whose comedies I like, specially the last one, Beautiful Lies, which however had disappointing ticket sales compared to his previous films, because it seems to me that this type of comedy based on sophisticated stories and meticulous, delicate dialogues, is something which is a little outdated now for the public. The only counter-example that I could find is Heartbreaker, which finds a kind of sentimentality which did not harm the success of the film. But as far as James L. Brooks is concerned, I have the impression that since the arrival of these more transgressive comedies, he has a more difficult status. Which is a bit paradoxical because Brooks is, in fact, the secret godfather of all new American comedy and is Judd Apatow’s idol. Furthermore, if success has become complicated for him, it is also because his scenarios have become more and more “Jesuitical.” His first films - I am thinking specially of Terms of Endearment and As Good As It Gets - were based on simple, extremely meaningful situations, with a strong weight of life in the characters. Now, I have the impression that, as his career progresses, he is moving towards something much more abstract, more speculative, a little disconnected from the world. Which can explain both why his films are very loved by some, but also go unnoticed by many others. It’s something that makes me a little sad but, at the same time, it’s quite consistent when we see the kind of comedies that are currently working. It gives the impression that the art of sophisticated and secret writing is no longer fashionable.

I’m surprised you say that he’s being undermined by the Apatow hype, because the people who defend James L. Brooks are pretty much the same people who defend Apatow.

Yes, but for the average viewer, I think that between a trashy comedy and a James L. Brooks comedy, there is an irreconcilable gap. And indeed, it is impossible, when you see the films of Judd Apatow (which I also like) to perceive the influence of James L. Brooks. It has nothing to do with it. Particularly for something which, for me, is the big question of comedy, and which is: what is the perfect rhythm of a film? I find that James L. Brooks has this ability to find the perfect rhythm for 90 minutes, while Judd Apatow not at all. And generally speaking, in current comedies, very often there are occasional hilarious scenes, but almost never an absolutely perfect rhythm from A to Z. Something like Wes Anderson, on the other hand, is looking for more of that, his films are not just a catalog of beautiful scenes and failed scenes, there is something more subterraneous. But Wes Anderson’s films don’t work very well either. I think that the question of the beauty of the background rhythm is a question that has become elitist: it is no longer a question that arises for the basic spectator.

It perhaps also comes from an ambiguity around the question of knowing what a comedy is. Are the specifications above all about making people laugh at sufficiently regular intervals, or is it also about telling a story? Apatow productions undoubtedly set themselves the primary objective of being really funny, and those of Brooks, Salvadori or Anderson, rather to tell a story or explore a theme in a comedic tone.

Absolutely. But what surprises me is that on this account is that if a comedy contains a certain number of successful scenes, the spectators do not seem to be bothered by the fact that there are also scenes that fail. For me, on the other hand, it’s something that bothers me and can completely prevent me from joining the film. Furthermore, I seem hyper critical, but I know very well that the basic rhythm of a comedy is hardest thing to achieve in cinema. And the fact that filmmakers often don’t succeed is a normal thing. But it’s still sad that it’s a challenge they’ve given up on.

In the process of reevaluation - in the French cinephile and critical circles - of the work of James L. Brooks, one of the highlights was the retrospective devoted to him at the La Roche-sur-Yon festival. And, for this retrospective, Jacky Goldberg’s presentation text began with a short history of the critical reception of Brooks’ films in France showing that he had been largely underestimated by Cahiers and Positif. Then, he paid tribute to you for the issue of La Lettre du Cinéma that you had devoted to the release of Spanglish in 2005. Do you feel that James L. Brooks can constitute a challenge in bringing out a sort of new critical line, which would stand out a little from what existed until then?

I don’t know the history of criticism around James L. Brooks, I just know that Terms of Endearment was known for being a tearjerker. At La Lettre du Cinéma, it was As Good as It Gets that we really loved and which, all of a sudden, crystallized a lot of things. Because it was miraculous what this film offered as a balance between the violence of the situations (Jack Nicholson really plays a very aggressive character), and something supremely fine in the writing. The mixture of the two, violence and finesse, left an impression on me. So then, as to whether James L. Brooks can be a kind of cinematic role model… Well, he has a bit of a Trojan horse side. That is, he is someone who was able to make very popular films, with films like these, very strong, but which, if we look at them more closely, also have something deeply secret, and something modest in the secret. And basically I don’t see much of an equivalent of that in American cinema part from him.

“Entretien avec Axelle Ropert” was originally published on fiches du cinema on April 1st, 2012. The interview was conducted by Nicolas Marcade. Translation by Jhon Hernandez